People with diabetes who use insulin with every meal are already well aware of the importance of counting or estimating carbohydrates to calculate their insulin doses.

However, some may be surprised to learn that both protein and fat can also have a significant impact on their blood glucose levels:

- Protein causes a delayed increase in blood sugar that is subtler than the effect carbohydrates have.

- Fat doesn’t directly cause blood sugar to rise, but it can both delay and enhance the effect carbohydrates have.

You can take your diabetes management to the next level by understanding the impact of these macronutrients. Dosing strategies for meals high in fat and protein can be complicated, but with practice, you can learn to combat the high blood sugar levels that come hours after a meaty meal.

How protein causes high blood sugar

Carbohydrates are easier to understand — the body quickly breaks them down into glucose. Even starches with a low glycemic index, like whole grains, can directly convert to sugars.

Protein is more complex. It isn’t made of sugars but amino acids, which don’t raise blood sugar directly.

But there’s more going on after you eat protein:

- As proteins are broken down into amino acids, they stimulate the release of glucagon. This hormone tells the liver to release stored sugars into the bloodstream.

- Additionally, our bodies can actually create glucose from protein in a process called gluconeogenesis.

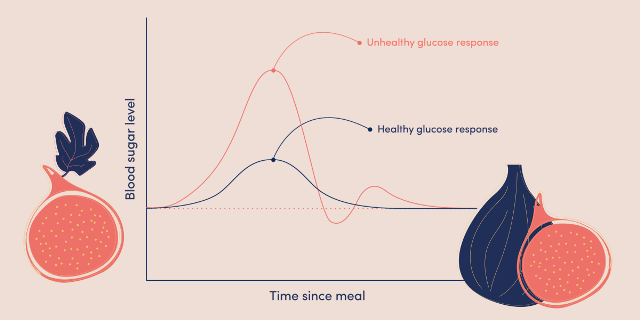

This conversion of protein into glucose happens over several hours, which can cause a slower and less intense effect on blood glucose levels. Still, the increase can be significant and can easily push your blood sugar out of the normal range.

A 2016 study that examined protein-only meals (without accompanying fats or carbs) found that only larger amounts (≥75 grams — about the size of a 12-ounce skinless chicken breast) caused a blood sugar increase. That rise started slowly, one to two hours after the meal, peaked between three and five hours later, and had a similar total glycemic effect as about 20 grams of carbohydrates.

How fat causes high blood sugar

Unlike protein and carbohydrates, fat is thought to have little direct impact on blood sugar. If you drank a glass of olive oil or ate a piece of butter, your blood sugar wouldn’t necessarily rise.

Many people with diabetes know this as the "pizza effect." Foods that combine large amounts of carbohydrates with large amounts of fat, like pizza, often lead to very frustrating and unpredictable delayed glucose spikes. When scientists at the University of Pennsylvania experimented with insulin dosing techniques for pizza, they found that participants who ate two or three slices of cheese pizza for dinner still needed insulin dosing up to eight hours later.

Fat slows digestion — something we've known for over a century.

After a high-fat meal, it takes the intestines longer to break down carbohydrates and for glucose to enter the bloodstream. Some studies have even found that large amounts of fat can actually lower blood sugar levels for a few hours after a meal.

But it’s not just that fat delays the spike in blood sugar from carbs — it also increases the amount of insulin you’ll need — perhaps because fatty meals can temporarily reduce insulin sensitivity.

Overall, it’s clear that larger amounts of dietary fat make insulin dosing much more complicated. And when you eat carbs together with large amounts of fat and protein, the effect is additive, resulting in the biggest delayed glycemic spike of all.

How to dose insulin for protein and fat

Many people with diabetes are instructed to consider only carbohydrates when deciding how much insulin to use. However, if you notice your blood sugar rising for hours after a protein- or fat-heavy meal, it may be time to consider those macronutrients in your diabetes management plan.

What’s the best way to dose for protein and fat?

We’ll outline a few strategies below, but the truth is that finding what works for you will require trial and error. Everyone is different, and different foods affect us differently.

From many studies on the topic, perhaps the most convincing statement comes from a 2021 systematic review of research literature, which concluded:

"There is no consensus on when fat and/or protein should be included in calculations, and there is no uniform algorithm for insulin therapy in this context."

In other words, there isn’t one perfect pattern that will work for every food or every person.

Adjust the timing of insulin delivery

After a large and complex meal, there are generally two related but different blood sugar peaks to manage:

- A rapid rise from eating carbohydrates

- A delayed rise resulting from mixing carbs with protein and fat

The ideal insulin dosing strategy prevents both blood sugar spikes, keeping you steady and within target the entire time.

An insulin pump is an excellent tool to handle this double challenge. Most studies we reviewed recommend using a dual-wave or extended bolus function, allowing users to deliver one large dose of insulin at the start of the meal, then slowly deliver the rest over several hours.

- The Penn State study on pizza found that the best method was: "Half of the insulin given as an immediate bolus right before the meal, and the other half slowly through the pump over the next eight hours."

- An Australian 2021 study on adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes concluded that a high-fat, high-protein meal was best controlled by giving 60% as a pre-meal bolus 15 minutes before eating, and the remaining 40% continuously over the next three hours.

- The Warsaw method recommends first starting with your normal pre-meal bolus for carbs using your usual insulin-to-carb ratio. The second dose, given after the meal as an extended bolus, is calculated by counting the total calories from protein and fat, dividing that total by 10, and applying your usual insulin-to-carb ratio to that number. Meals with 100 calories from fat and protein are counted as 10 grams of carbs and require extended dosing over three hours. Meals with 300 or more calories are counted as 30 grams of carbs and require extended dosing over eight hours.

If you don’t use an insulin pump, it’s harder because the after-meal insulin dose for fat and protein often must be given at once, rather than spread out over several hours.

So, if you’re injecting multiple times a day, it’s often recommended to take a second dose one to two hours after the meal — but the timing can vary widely. Some people know from experience they need to wait even longer; others wait until they see their blood sugar start to rise. Some give multiple smaller doses to flatten out the insulin’s peak action.

Adjust the total amount of insulin

Don’t forget that both fat and protein can increase your total insulin needs.

Several studies and guidelines we reviewed agree that one gram of protein should be considered roughly 20% as effective as a gram of carbs. That is, if you dose 1 unit of insulin for 10 grams of carbs, you might try dosing 1 unit of insulin for 50 grams of protein. (However, if you follow a low-carb diet, your protein might require much more insulin than this, as explained below.)

An Australian study found that participants who ate a breakfast high in fat and protein needed a total of 140% of the insulin predicted by the insulin-to-carb ratio alone. Another trial, also from Australia, found that the ideal dose for a high-fat, high-protein meal required 130% of the insulin predicted by the insulin-to-carb ratio. Other estimates we reviewed were in the same range.

Closed-loop systems

These ingenious devices, which combine an insulin pump and CGM with an algorithm that automatically adjusts insulin delivery, can reduce much of the math and stress involved in insulin dosing decisions.

A closed-loop system can detect and prevent delayed glucose rises without any user input. That’s hard to beat! Some systems have an extended bolus option even when using closed-loop mode, and most have an extended bolus feature in manual mode.

Regular human insulin and protein

If you don’t use an insulin pump and struggle to handle delayed blood sugar rises from protein, here’s an unusual idea.

Many dietitians following low-carb and keto diets, following advice from Dr. Richard Bernstein, use regular human insulin for bolusing protein-heavy meals. Regular human insulin is an older generation of rapid-acting insulin. It acts much more slowly and gradually than newer insulins, making it worse at stopping sharp spikes from carbs, but supposedly better at matching the slower, delayed blood sugar effect from fat and protein.

Some people with diabetes on low-carb diets always use a bolus of regular human insulin to cover protein intake. Others only find it necessary for particularly protein-heavy meals. Still others may combine a bolus of modern rapid-acting insulin (for the carbs in the meal) with a bolus of regular insulin (for the protein). Regular insulin can be given as a pre-bolus, at the start of the meal, or after it, depending on the expected blood sugar; the best timing will vary from person to person and even from meal to meal.

Protein has a different effect on people following a low-carb diet

From anecdotal reports on forums, many who stick to low-carb diets notice more dramatic blood sugar spikes from protein, resulting in a greater need for insulin for protein-rich meals.

It turns out there’s a scientific explanation. The rate of gluconeogenesis actually increases in people who eat fewer carbohydrates, meaning their bodies create more glucose from the protein they eat. This change can become especially noticeable when people first switch to a low-carb diet and discover that meat affects their blood sugar differently than before.

Conclusion

While every diabetes patient using intensive insulin management is taught how to calculate a bolus for carbs, the effects of fat and protein on blood sugar aren’t as well known. The truth is, meals high in fat and/or protein can create large delayed blood sugar spikes and often require additional insulin.

Patients who struggle with high-fat and high-protein meals are usually advised to use two boluses to neutralize the early glucose rise from carbs and the later glucose rise from the complex mixed effects of protein, fat, and carbs. But getting the details of timing and amount of bolus right will almost certainly require some experimenting and trial and error.

Source:

DiabetesDaily